LI Jiaqi: With Open Eyes: Curated by GAO Yuming

BONIAN SPACE is pleased to announce the first solo exhibition of artist Li Jiaqi, titled "With Open Eyes," running from July 20 to August 18. Curated by Gao Yumeng, the exhibition features over ten paintings created by the artist in recent years.

Gaze and Its Return

By Gao Yumeng

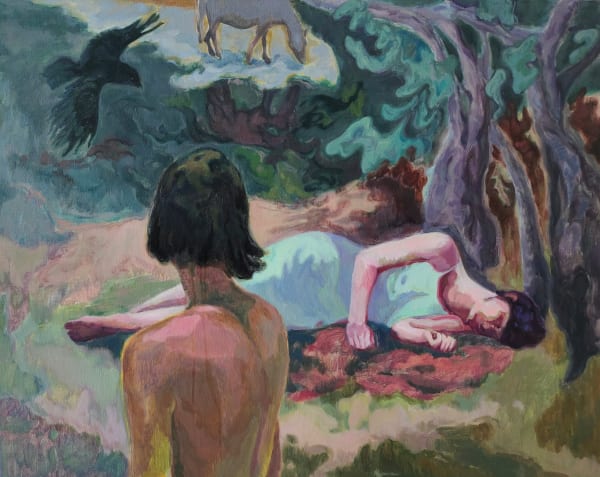

Li Jiaqi's creation begins with the "self" confronting internal contradictions and the complex external environment. She symbolically depicts the subconscious world with flowing lines and colors. The characters in her paintings peel away various forms of the self under the gaze of external others—isolated, suspended, struggling, and escaping—eventually dissipating into a suggestive fictional nature.

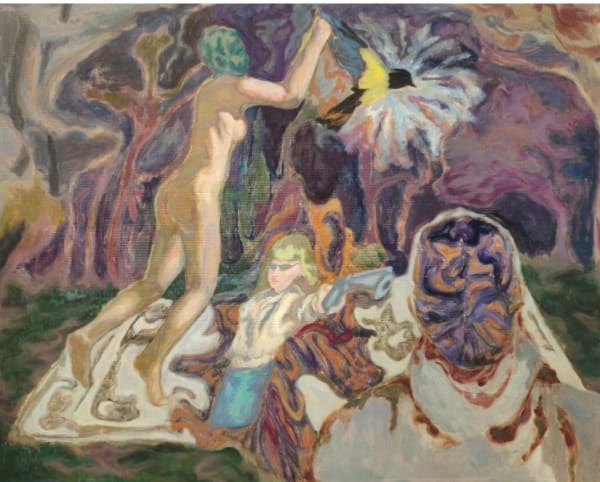

However, this subject's dissolution in complexity is deceptive. In A Bird's Farewell, the protagonist's multiple selves are montaged within the frame. The naked body is isolated and suspended in the foreground, while the realistic self floats behind. The face, initially veiled in a layer of floating cyan mist, remains hidden. Speech is silent, and thoughts are entrusted to the departing bird. Induced, the viewer's gaze flows and rests upon this timeless, narrative-less image. Inside the frame, the self is being gazed at, while outside, the gaze is cast by the viewer—the power thus far belongs to the viewer.

However, at the moment the viewer's gaze is captured, the artist decides to awaken "her," granting her eyes to gaze outward. Thus, she looks at us, and we are compelled to meet her gaze. The viewer, immersed in scrutinizing and seeking visual pleasure, realizes they too may be observed by others, transforming from a subject into an object in the eyes of another. As Li Jiaqi states, "I place people and nature in a fabricated virtual realm, using the role reversal of gaze subjects and objects or creating gaze traps to capture the truth behind it, hoping the viewer resonates with the confrontation with the painting."

From Dürer's self-portrait to Manet's Olympia, from German Expressionism to Surrealism and Pop Art, the "the return of the gaze" has traversed numerous moments in art history, witnessing the self of the gazed object being manifested through provocative, deterrent, or enticing eyes, or forcing the gazing subject to reveal existence. Sartre, in "Being and Nothingness," delves into "le regard" (the gaze). He believes that the gaze possesses immense power; when an individual is observed by others, they feel deeply exposed and vulnerable, realizing they have become an object in others' eyes rather than an independent subject. This gaze is not just a simple look but a force that can influence and define the existence of the observed. It reveals the other's power over the self, making the individual aware of being objectified, feeling deprived of self, prompting reflection on the meaning of their existence.

This externalization process of self-awareness shifts us from "being-for-itself" (être-pour-soi) to "being-for-others" (être-pour-autrui). The deprivation of freedom and autonomy brought by the gaze and judgment of the other is where "hell is other people." The gazed chooses to look back. They thus cease to be merely passive observation objects, actively participating in the visual exchange. This counter-gaze helps the gazed regain self-feeling, avoiding being possessed and defined by the other's gaze.

"Humans, as social animals, born in groups, inevitably face the question of how to position themselves in the collective, forcing me to continually seek answers to this question."

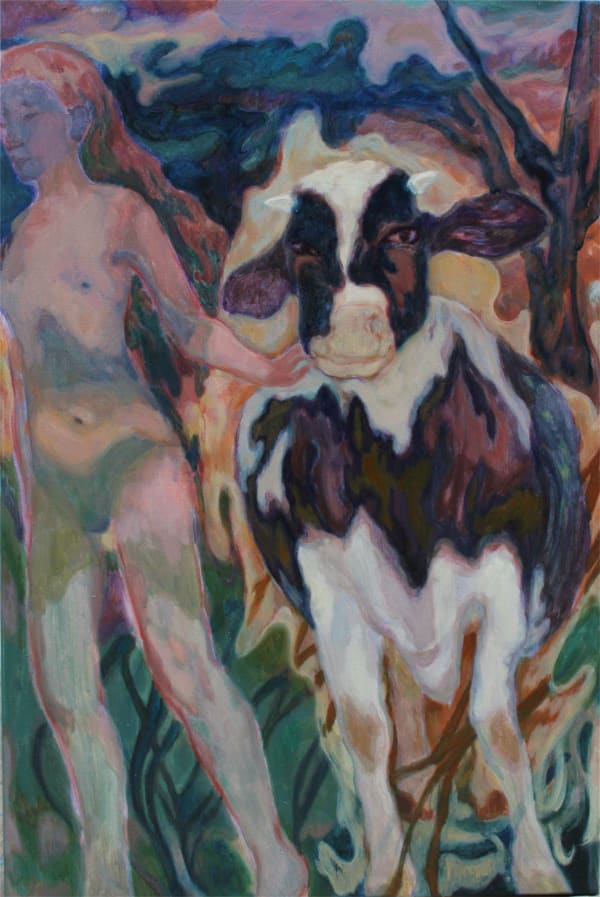

Initially, the animals in Li Jiaqi's works often have symbolic meanings. For example, Black Sheep represents the rejected and isolated self, symbolizing individuals who cannot be accepted or understood in mainstream society. The orderly white sheep symbolize the mainstream and norms, with the contrasting existence of the black sheep breaking this harmony, revealing the conflict between self-identity and social identity. Similarly, Mute Bird symbolizes the self forced into silence and suppression by social environment and gender norms, possessing wings for flight but trapped in a silent world. Likewise, there are the Blind Cow, Lost Deer... All separated at moments when self-consciousness is squeezed and wandering. Through contrasting portrayals in different forms, the self is continually explored and redefined.

Gradually, the meanings carried by these animal images become more flexible and diverse, serving as a medium for dialogue between the artist and the external world. In Black Hand, she deeply reflects on violent acts and the indifference of onlookers in social events, depicting the perpetrator's hand reaching toward the innocent in a particularly striking and glaring black, directly condemning the violence. The black backs of the onlookers imply societal complicity and indifference towards the weak. Conversely, she replaces the victim's image with a sheep symbolizing innocence and sacrifice, attempting to alleviate the visual violence.

In the blurred outline of the sheep's head, the artist once again endows the passive object with a face and a gaze. The weak may finally use a gaze to mildly counterattack. By depicting the act of gazing, she seeks to use the power of the gazer to turn the gazed into an object, evoking a moral and ethical relationship. According to philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, a face signifies a command: "Thou shalt not kill." Encountering the face of the other becomes an ethical event, compelling the subject to transcend their interests and prioritize the needs and rights of the other. This returning gaze pushes us into an ethical relationship, demanding we refuse to participate in the murder of the weak—not ignoring or neglecting them, but becoming their partners and giving them respect. It breaks down self-centeredness, reminding viewers to bear the infinite responsibility towards others when facing violence and injustice.

Do animals have "faces"? Perhaps in her new works, Li Jiaqi continues and echoes Levinas' exploration. Derrida, in "The Animal That Therefore I Am," through the experience of being naked in front of a cat, demonstrates that animals, through their existence and gaze, can influence the human subject, challenging the traditional philosophical dichotomy between humans and animals, emphasizing that animality is an essential part of humanity.

This question seems overly complex and controversial, yet "the horse" indeed gazes at us, "Shuangshuang" (a cow) gazes at us, and in her new work Moon in the Water, the monkey group" also faces us with their vivid faces, gazing at us with unavoidable eyes. If "Monkey Fishing for the Moon" uses animals as metaphors for human behavior, then in this work, the anthropocentric perspective is inverted. People rush towards the reflection of the moon in the water, while now it is the monkeys who gaze at us from the painting with a satirical look: "Do you see reality or merely your reflection?"